How did Phung Ton die?

by robbie | June 1, 2010 11:25 am

PHNOM PENH, Cambodia – On a Sunday morning in March 1975, Phung Ton, one of Cambodia’s most esteemed academics, packed his bags and prepared to fly from Phnom Penh to Geneva, Switzerland, under different circumstances a quite unremarkable trip. The 54-year-old, a former rector of the University of Phnom Penh who had held a series of government posts, was no stranger to official business abroad – the all-day conferences, the dinners with dignitaries, the nights alone in opulent hotels. He was used to being separated from his wife and children for weeks at a time.

During that spring, however, unremarkable endeavours were complicated by the ongoing civil war between the Lon Nol government and communist insurgents. Armed clashes were fast closing in on the capital. In the hours before Phung Ton was to fly out, several rounds of aerial bombardments struck not far from Pochentong Airport. His airline, Air Cambodge, instructed passengers to gather at its office near Central Market, from which they would be escorted to their flights under tight security rather than drive to the airport themselves.

Im Sunthy, his wife of 20 years, opted not to go with him. They bade farewell at their house, a villa near the Independence Monument in the city centre. She massaged his back as he lay face down on their bed, and when he had gone she holed up in his office, where she waited for his call from Bangkok to inform her that he had exited the country safely.

“I was waiting for his call until seven pm, and finally he called me,” she recalled, 34 years later. He told her to look after her health, and not to send the children to school if the intensity of the shelling increased. “He said I should observe the situation and make a decision accordingly as to whether the children should be sent to school or not.” After a few minutes, she cut him off. “I did not want him to waste money on the telephone bill, because we were strict about expenses.” That would be their last conversation.

One month later, the insurgents captured Phnom Penh two weeks after the resignation of Lon Nol, a general who had come to power in 1970 by overthrowing then Prince Norodom Sihanouk.

It was Sihanouk who gave the communists their now infamous appellation—the Khmer Rouge, Red Khmer in French—and used repressive tactics to force them underground in the 1960s. Following his overthrow, however, the movement benefited from the ineptitude of the Lon Nol government, which was widely viewed as corrupt and bent on preserving a feudalist social order that separated a small group of urban elites from a nation of impoverished farmers.

As with other communist movements, the Khmer Rouge were headed mainly by teachers and writers, some of whom had first been exposed to Marxism-Leninism while studying in Paris in the 1950s. Their Brother No 1, Saloth Sar, alias Pol Pot, sought to turn the clock back to ‘Year Zero,’ by which he meant abolishing religion and culture as well as any trace of modernity. In this regard, his revolution can be seen as a rejection of both the past and the future in favour of a present modelled exclusively on his own principles.

Top cadres preached self-sufficiency, calling for a mode of extreme collectivisation that had at its core a network of massive irrigation projects built on the backs of peasants. What they put into practise, however, was a regime notable for its cruelty, its economic folly and, finally, its apparent eagerness to devour those very peasants who had been promised they would prosper during its rule. After summarily executing officials and soldiers aligned with Lon Nol, they redistributed the population into a network of labour cooperatives and attempted to bring their vision of agrarian utopia to life, while cutting themselves off from the outside world and Western cultural influence.

When it became clear that his goals were unrealistic, the ever-paranoid Pol Pot assumed the existence of an internal plot against his Communist Party of Kampuchea, and filled its prisons with cadres who had, often unfairly, been branded enemies. Once incarcerated, they endured torture ranging from rattan stick beatings to suffocation to more extreme abuses. In one procedure, called the Victory Pole, four detainees were tied around a pole, all facing outward, and a guard shot one in the head, leaving the other three spattered in brains.

After writing ‘confessions’ that affirmed Pol Pot’s suspicions, many were executed at the ‘killing fields,’ often by the blow of a farming tool to the back of the head. At the Choeung Ek killing fields outside Phnom Penh, babies born to cadres who had fallen out of favour were swung by the legs and smashed into trees.

Meanwhile, peasants everywhere died of starvation, overwork and—because nearly all the doctors had been killed— disease. All told, nearly two million Cambodians perished, roughly a quarter of the population when the regime came to power.

The question of how the Khmer Rouge so effectively turned Cambodia against itself has, not surprisingly, been the subject of much debate in the three decades since they were run out of the capital. Various theories point to the culpability of communist ideology, American involvement in the Vietnam War and pure, unadulterated evil, but, ultimately, answers are elusive.

So are answers to another question: who bears responsibility for their atrocities? Until February 2009, when the Khmer Rouge tribunal’s first trial—that of Kaing Guek Eav, alias Duch, the regime’s top prison chief—opened in Phnom Penh, not one senior leader had been made to answer for his or her crimes in a court of law.

****

The establishment in 2006 of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, a hybrid court tasked with prosecuting senior regime leaders and “those most responsible” for Khmer Rouge crimes, was hailed by its architects as a crucial step towards eradicating the much-maligned “culture of impunity” that pervades the country today. Along with corruption and free speech restrictions, the current government of Prime Minister Hun Sen, a former Khmer Rouge soldier who defected to avoid being purged, is routinely lambasted for its weak justice system, which is perceived to be completely in the hands of what the rights watchdog Global Witness has termed a “kleptocratic” elite. The court has been sold to its backers in part for its mechanism for addressing this, as well as for advancing the loftier, more nebulous goal of national reconciliation.

Until February 2009, not one senior leader had been made to answer for his or her crimes in a court of law.

From the outset, however, some observers have questioned whether the court can provide a form of so-called ‘transitional justice’ appropriate for Cambodia. Defined as any response to systematic or widespread violations of human rights, the concept of transitional justice includes, in addition to criminal prosecutions, memorials, reparations programmes and non-judicial commissions designed to establish historical records of atrocities rather than punish those who committed them. In South Africa, for example, the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission granted amnesty to nearly 850 cooperating petitioners.

Much criticism has concerned the court’s ability to serve victims. Unlike in a truth commission, a perpetrator testifying in a criminal trial such as those now unfolding in Cambodia is necessarily on the defensive, eager to deny or at least downplay his or her guilt in the hope of securing an outright acquittal or a mitigated sentence. This almost invariably complicates a court’s fact-finding mission, something that is particularly true at the Khmer Rouge tribunal, where all five accused presumably know far more about the regime and its operations than lawyers, judges and witnesses. Moreover, because the fate of the accused hangs in the balance, the focus in a criminal trial is shifted to his or her actions and statements, and away from the testimony of those whose suffering is ostensibly being acknowledged.

Tribunal sceptics seem to have only been buoyed by the Duch trial, which concluded in November and is awaiting verdict. During nearly six months of hearings last year, victims watched from the public gallery as the accused, sitting in the dock behind a wall of glass, offered a version of his role in Pol Pot’s security division that came across to many as abridged and self-serving. Those expecting a full accounting had to settle instead for an awkward marriage of remorse and professed ignorance of the specific crimes— torture, killings, vivisections—he allegedly oversaw. As the case entered closing arguments, Nic Dunlop, the photojournalist who in 1999 discovered Duch a few years after he had defected, lamented the extent to which the prison chief had been permitted to dominate the proceedings at the expense of his victims. “There was an expectation raised,” he told me. “The [victims] believed that they would be able to look this man in the eye and finally ask him direct questions about their loved ones and experiences. Some had that chance. But these people were waiting for what was to be their day in court. Not Duch’s day, but theirs.”

****

For Phung Ton’s family, the Khmer Rouge revolution began quietly. In compliance with a round-the-clock curfew, Im Sunthy and her children spent the morning of 17 April 1975 in their grandfather’s villa, which was located on the same compound as theirs.

Phung Sunthary, the oldest child and only daughter of Phung Ton and Im Sunthy, remembers standing in the front window watching soldiers and civilians pass by. All of them, even the defeated Lon Nol troops, were jubilantly celebrating the Khmer Rouge victory and the end of the civil war.

Two of her younger brothers ran out to join the crowds cheering the tanks and trucks as they rolled down Norodom Boulevard. Despite predictions of a bloodbath, the scene was relatively calm, with some of the Lon Nol soldiers setting their guns in piles and obeying the conquering army’s orders.

By mid-morning, however, the mood had turned. The sound of gunfire resumed. Soldiers in the streets were joined by families who had been forced from their homes and ordered to leave the city.

“A Khmer Rouge soldier came to the window and told us to get out of the house,” Phung Sunthary recalled. “We didn’t know where they wanted us to go. So we put some clothes in a bag and left.”

Along with nearly every other resident of Phnom Penh, including hospital patients kicked out of their beds, the more than 30 members of Sunthary’s family began marching to the city’s outskirts. The family was eventually broken up and sent to various provinces to be integrated into communities composed mainly of ‘base people,’ the rural peasants who were to assume leadership roles in the new society. As Phnom Penh natives, Phung Ton’s relatives were ‘April 17 people,’ the ideologically suspect urbanites.

The April 17 people faced more taxing living conditions and were given more strenuous jobs than their rural counterparts, part of an effort to crush the former group’s ‘bourgeois’ tendencies. Im Sunthy, who had previously worked as a schoolteacher, was tasked with fetching water from a nearby river for the kitchen of her work cooperative. This consumed much of her days.

“And when there was no food,” she recalled, “we talked about eating chicken with some kind of ginger sauce. After they heard that we were talking about this with our children, we were taken to be re-educated, and we were warned not to ever speak about eating bourgeois food like that.”

One day, one of her sons who had been allowed to stay with her was spotted trying to catch a fish to supplement his daily ration. “After my child committed that alleged wrongdoing and was warned and punished, I was called to ‘build myself.’ I didn’t understand the words ‘building myself.’ I was told to sit down on the paddy’s dyke, and I was told that I was a liberal person. I was ill-disciplined. I had grown used to living in the city.”

Her daughter, Sunthary, was assigned to one of the regime’s female ‘mobile work units,’ which travelled among farming cooperatives and irrigation project sites. Her life was difficult but endurable. “Starvation, forced marriage, these kinds of things I could escape,” she said. “Luckily, I could avoid being raped.”

But she was not entirely free from anxiety. Towards the end of 1977, she saw visions of her father, who’d been saved by his flight to Europe, one night as she slept. “I had a vivid nightmare, and I saw my father. His body was swollen. I could not see his face. He was speechless, and I did not know why he did not say anything.” The visions stayed with her, and she eventually asked her unit chief if she could travel to visit her family. When she arrived she told her grandmother about the nightmare. “I was afraid my father was in big trouble because I had seen him in the dream and he was not in good shape,” she said. Her grandmother, who, like everyone else in the family, had heard nothing from Phung Ton, calmed Phung Sunthary down and instructed her to return to the work unit. It would be several years before she learned that hers was a dream from which there would be no waking.

“I don’t know what to expect back home, but I want to return there, if only to be reunited with my family, because I have not heard from them in nine months,” Phung Ton wrote in a farewell letter to a friend in Paris as he prepared to return to Cambodia in December 1975. Instead of calling him home right away, the new regime had, in May of that year, temporarily transferred him from Geneva to Paris, where he had been living in a studio apartment in the 13th arrondissement.

Phung Ton appeared to have little interest in communism, having assumed several civil servant posts under Lon Nol, whose fierce anti-communism earned him American backing. In the spring of 1975, however, he wrote in a letter of how he had decided while in Europe to join the National United Front of Cambodia (FUNK), a movement opposed to Lon Nol and purportedly led by Sihanouk. (In fact, this was a ruse used by the highly secretive Khmer Rouge to conceal their true leadership.)

The letter suggests that this decision was not prompted by any change in his views but rather by a careful reading of the political winds. “I have many Cambodian friends, and almost all of them have advised me to join the FUNK,” he wrote. “I have heeded their advice, and have requested to join the FUNK. I had no choice, as you know.”

That same letter refers to “rumours concerning the forced evacuation of Phnom Penh” that were circulating among the many Cambodian civil servants, students and diplomats living in Paris in 1975. Desperate for news of their families, and no doubt comforted by Sihanouk’s presence at the head of the FUNK, many pushed these rumours out of their minds and heeded the Khmer Rouge call to return and rebuild the country. Phung Ton joined their ranks in December 1975, travelling via Beijing and arriving in Phnom Penh on Christmas Day.

Little is known about what happened to him after that. His Khmer Rouge prisoner biography states that he was sent to the prison camps K‑5 and K‑6 upon his arrival. Both housed intellectuals who had returned from abroad. “He had conflicts with others and the Central Committee,” the biography states, though there is no elaboration. Then, in December 1976, he entered Tuol Sleng, or S‑21, the Phnom Penh prison that would become the single most potent symbol of Khmer Rouge brutality.

A converted high school, Tuol Sleng was run by Duch, a former maths teacher whose efficiency betrayed both meticulousness and unbridled revolutionary zeal. During the regime years, it housed an elite subsection of the regime’s socalled enemies: intellectuals, Westerners, Vietnamese prisoners of war and—by far the dominant group—high-ranking cadres who Pol Pot believed had turned against him. Upon arrival, they were processed at a central administration and archives building, in which their photographs were taken and their basic biographical information recorded, before being sent to one of four main detention halls. Interrogation houses were located just outside the entrance, while the burial ground was located behind the detention halls— that is, until the body count became so high that Duch felt compelled to establish the Choeung Ek killing fields some 15 kilometres away.

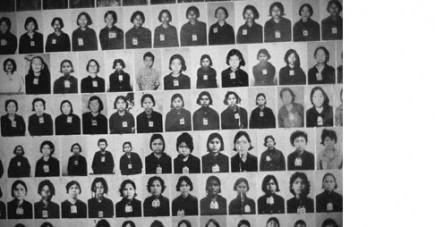

Two things set Tuol Sleng apart from other security centres administered by the Santebal, the Khmer Rouge secret police. The first is that it was the hub of security operations, housing prisoners from throughout the country who were viewed as too important to be detained in the provinces. And the second is that it is by far the bestdocumented cog in a sprawling detention machine. When the Vietnamese defeated the Khmer Rouge and overtook Phnom Penh, Duch did not have time before fleeing to dispose of the extensive records his staff had accumulated, and many of them—including thousands of prisoner mug shots—are now available for perusal at the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum.

The historian David Chandler has dubbed Tuol Sleng “an anteroom to death,” a point driven home even more so by these mug shots than by the graves in the courtyard, the impossibly small brick cells or the beds to which prisoners were chained. Nearly all of them show a Cambodian wearing black pyjamas, the revolutionary uniform, staring straight into the camera. Smiling girls are next to frowning old men are next to sobbing little boys are next to mothers holding children, and the only thing that connects the images is the fact that, even before the flash came, the fate of their subjects was sealed. Only ten or so of the estimated 16,000 Tuol Sleng prisoners made it out alive.

The last document that mentions Phung Ton, dated 6 July 1977, states that he had been suffering from numbness, fatigue, and unspecified heart and respiratory problems. There is a chance he would have been considered important enough to receive medical care, but this almost surely would not have been helpful; the ‘medics’ at Tuol Sleng were children with no training who gave rabbit pellets to sick prisoners or drew blood from them, sometimes so much they died on the spot.

By July, he would have been incarcerated for nearly seven months, an exceedingly long time at a facility from which most prisoners were transported to the killing fields right after their confessions were completed. This lends credence to the theory that he was not tortured and executed but instead succumbed to his illnesses. All Sunthy and Sunthary know for sure is that he died.

For a while they didn’t even know that. After returning to Phnom Penh in 1979, they discovered that, miraculously, every other member of the immediate family who had been in Cambodia when the Khmer Rouge came to power had survived.

The family heard a series of rumours, including that Phung Ton had been spotted heading towards Siem Reap in the summer of 1979, and that he had been working at a technical institution of some kind in the capital. As they went about rebuilding their lives, they held out hope that he would return. More improbable reunions were occurring all around them.

One evening later that year, they stopped to buy some palm sugar while walking home from their jobs at the Phnom Penh port. The vendor, Sunthary recalled, wrapped it in a strip of paper that caught their attention because it had writing on it—the first writing they had seen since 1975 due to Pol Pot’s publishing blackout.

Sunthary discerned it was a list, with accompanying photographs, of people who had been killed at Tuol Sleng,

“After I unwrapped the piece of paper more,” she recalled, “I saw a snapshot of my father along with some other victims’ photos, and under his photo his name was written. But I could not believe that it was his photo. We didn’t know that people had been killed everywhere. But when I saw that piece of paper, then I realised the existence of S‑21.”

****

Almost immediately after Dunlop found him, Duch, a converted Christian, expressed a willingness to discuss the horrors of the Khmer Rouge years, and seemed resigned to the fact that his own misdeeds at Tuol Sleng would one day be aired publicly. “It is God’s will that you are here,” he said at the time. “Now my future is in God’s hands.”

Ten years later, on the first day of substantive hearings in his trial, he delivered a lengthy confession and apology. “I would like to apologise to all surviving victims and their families who were mercilessly killed at S‑21,” he said. “I say that I am sorry now, and I beg all of you to consider this wish: I wish that you would forgive me for the taking of lives, especially women and children, which I know is too serious to be excused. It is my hope, however, that you would at least leave the door open for forgiveness.”

Duch’s trial came first partly because of his apparent candour. The other four leaders detained at the tribunal—Brother No 2 Nuon Chea; Head of State Khieu Samphan; Foreign Minister Ieng Sary; and his wife, Social Action Minister Ieng Thirith—have refused to apologise or cooperate with investigators, remaining defiant despite the extensive evidence against them. A speedy conviction of Duch, observers argued, would surely be the quickest way to present Cambodia with some scrap of justice, however overdue.

Sunthy and Sunthary were among the 90 direct or indirect victims allowed to join the case as civil parties, meaning they were given legal representation as well as a chance to testify.

Sunthy went first. Because she had found the proceedings to be emotionally distressing, at one point fainting in the public gallery when a photograph of a detainee’s bloodied corpse was placed on a projector, a medical attendant sat beside her, and she kept her statement brief.

Then it was Sunthary’s turn. She expanded somewhat on the character sketch given by her mother, but the objective of her statement was to elicit the information both women were seeking. “I have heard the testimonies of the expert witnesses, the testimony of the accused, the lies, the excuses. And I can see that the accused has tried to avoid responding to some particular questions,” she said. “Until now, I have not yet obtained the information relating to my father’s fate.”

She told the court that she had three questions she wished to put to Duch, adding, “If the accused still does not want to respond to these questions, then I think it is better if he never again says he is remorseful.”

She asked her first question: “Who made the decision to kill my father on the 6th of July, 1977, or a little bit after that?”

Duch, wearing a Ralph Lauren dress shirt and slacks, his customary courtroom attire, stood up to respond. “Although I have the deepest respect for my former professor, I do not have any answer to that at this time, and that is the truth,” he said.

Second: “What types of torture were inflicted upon my father?”

Duch said he didn’t know for sure, but that he believed Phung Ton had not been tortured at all.

Last: “Who made the decision to transfer my father to S‑21?”

Again, Duch said he didn’t know, though he vowed to “do my best to help you in your quest for the information on the fate of your father.”

He also offered, almost in passing, the following advice: “Maybe Mam Nai is the only person who can actually shed light on the exact details of his fate.”

****

Duch was referring to a former teacher turned revolutionary, alias Chan, who served as Tuol Sleng’s interrogator, a role for which he was perfectly suited.

At well over six feet tall, Mam Nai towers over the average Cambodian. He is distinctive also for his light features, large ears and full lips. After observing him interrogate prisoners in one of the remaining Khmer Rouge strongholds in 1990, the journalist Nate Thayer, who has also interviewed Pol Pot, told Chandler that Mam Nai “was the most frightening looking character” he had ever seen.

The thought that Mam Nai might possess information about Phung Ton’s death had occurred to Sunthary and Sunthy long before Duch suggested it. Mam Nai, like Duch, had graduated from the Pedagogy Institute while Phung Ton was its director. Phung Ton signed all of the diplomas, so Mam Nai would almost certainly have known who he was. And Mam Nai had finished first in his class of 200, meaning there is a good chance the two met at some point.

By far the most promising link was the fact that Mam Nai had apparently participated in some capacity in Phung Ton’s interrogation. His notes and signature are on the professor’s confession.

Mam Nai, who lives with his second wife and children close to the Thai border in Battambang province, was called to testify as a witness in July, presumably so he could shed light on the operations of S‑21 and Duch’s role in them. From the very outset, however, he made the process difficult, at several points opting not to answer questions due to self-incrimination concerns.

When he did answer, his responses seemed crafted to downplay his own significance within the security system. He described himself as “just a plain and simple interrogating cadre” who, while at M‑13, a prison in Kampong Speu province, had been tasked with planting potatoes and occasionally observing Duch interrogate detainees. “Then [Duch] asked me to interrogate the less important people at night,” he said. He later added that the interrogation process involved merely obtaining biographical information, and that he did not use torture.

This statement blatantly contradicted his own interrogation notebooks, which were recovered after Tuol Sleng closed down. In them, Mam Nai justified the use of torture in concert with political pressure—what Duch called “playing politics”—to yield inculpatory confessions. “Take their reports, observe their expressions,” he wrote. “Apply political pressure and then beat them until [the truth] emerges. Thinking only of torture is like walking on one leg—there must be political pressure [so that we can] walk on two legs.”

Asked if he had any regrets about the 1.7 million deaths for which the regime is blamed, Mam Nai told the court, “I believe that there were some good people, and there were some people who committed wrongdoings. Through my observations, there were less good people than the bad people. So I am regretful for those small groups of people.”

After the judges concluded their questioning, the floor was turned over to the civil party lawyers. The lawyer representing Sunthy and Sunthary, Silke Studzinsky, immediately brought up Phung Ton. But Mam Nai continued to deflect questions, saying he could not remember anything about the professor’s time at Tuol Sleng. He eventually conceded, following extensive prodding, that he conducted Phung Ton’s interrogation and signed his confession, but he said little else.

As with all witnesses, Duch was permitted to respond to Mam Nai’s statements. He accused Mam Nai of lying, or of at least concealing the truth.

“Please, please don’t be afraid,” he pleaded with his former subordinate. “Just tell the truth. You cannot really use a basket to cover the dead elephant, so don’t even attempt to do that.”

As Duch spoke, both Sunthy and Sunthary could be heard sobbing from the gallery.

“So when it comes to Professor Phung Ton,” Duch continued, “we both admit that he was our teacher. I don’t want to elaborate further on why I liked this professor, but I’m here to talk right before the civil parties, and the daughter of my teacher. Here we are now trying to tell the truth of what happened to him, the victim, because the world and the Cambodian people are looking forward to hearing the truth.”

When Duch finished, Studzinsky asked Mam Nai, once again, whether he could share anything about the fate of Phung Ton. Upon hearing the question again, Mam Nai broke down crying.

Before ending the session, the lead judge asked Mam Nai one last time if he could answer Sunthary’s questions. “I think if I am asked to bring further information,” Mam Nai responded through tears, “I think it is impossible, because it’s like shooting something in a dark night.”

****

A few weeks after closing arguments concluded, Sunthary acknowledged being disappointed that neither Duch nor Mam Nai had revealed more about her father, though she said Mam Nai’s contrition seemed more authentic. “Duch’s tears, his crying, that’s a lie,” she said. “But Mam Nai’s are real tears.”

Perhaps in a one-on-one interview outside of the tribunal, she said, Mam Nai might be willing to share more information.

I then told her that I planned to interview Mam Nai in Battambang, and asked whether there was anything she wanted me to say to him on her behalf. She said I should ask him the same three questions she had posed to Duch.

While some regime figures have been increasingly open to interviews in the 12 years since Pol Pot’s death—which occurred under mysterious circumstances in 1998 after holdout cadres turned against him and placed him under house arrest—Mam Nai has limited his contact with journalists. His lawyer, Kong Sam Onn, declined to give out his client’s mobile number, but said he might be willing to speak if I showed up at his home.

Western Cambodia is home to all of the former Khmer Rouge strongholds, some of which remained effectively independent from the government in Phnom Penh until 1998, as Hun Sen worked slowly to convince former cadres to defect. It was from here that Pol Pot waged his revolution, and it was to here that he retreated following his defeat at the hands of the Vietnamese. Former revolutionaries populate entire villages. In many areas, they speak proudly of the strength their leaders once wielded even while disavowing any connection with the policies that drove their country to ruin.

The trip to Mam Nai’s village, Chamkar Lhong, takes four hours by car from Battambang town, Cambodia’s second city. His house, a red, two-storey farmhouse structure with a roof of blue zinc, sits at the end of the only road in Chamkar Lhong. There are banana trees out front and a chicken coop in the back. It is the biggest house in the village.

Sitting near the front door when we arrived was Mam Nai’s daughter-in-law, So Teavy. She said we had just missed him—he had left that morning to work on a farm owned by the family “about 50 or 60 kilometres away.” We asked for directions. She said she had never been there. We asked for a number for Mam Nai or anyone with him. She said no one at the farm had a phone. We told her we had a gift for her father-in-law. She smiled but said nothing.

Then an older woman walked over from a house down the street. “Who is this here?” she asked. I recognised her as Mam Nai’s wife, Khun Lak.

We identified ourselves. She was not pleased. “When I saw your car I thought you were my son. If I had known you were not my son I would not have allowed you into this village. All the foreigners who come here just want to get more information from my husband. But he already spoke at the court for two days! He said enough. No more information. So don’t even try.”

Worried she would send us away immediately, I asked about a subject that I thought had as a good a chance as any of eliciting a response: Last year, the court announced that it intended to go forward with investigations of at least five more Khmer Rouge leaders, a plan that was immediately criticised by Hun Sen, who warned that civil war might break out.

“I support Hun Sen’s idea not to allow more arrests,” Khun Lak responded. “It’s correct. Because for the people living here along the border, we’re all Khmer Rouge. Not just here, but in other provinces too. So if they want to sentence more people, they’ll have to bring all of us to the court.

“Write this down,” she added. “We are not the leaders. We were just at the low levels of the Khmer Rouge. The only reason we will go to the court is to be a witness.”

I enquired again about her husband, who I suspected might be somewhere on the property. I told her there were questions that had gone unanswered during his two days of testimony, specifically relating to Phung Ton. I said we had brought some notes from Phung Ton’s daughter that she hoped would jog Mam Nai’s memory about the death of her father.

“No,” she said. “Even if you meet him, he will not talk. Or he’ll say the same things he said at the court.

“I want to say the following to Phung Ton’s daughter: You have no right to ask about that.”

“And I want to say the following to Phung Ton’s daughter. Who do you think you are? Only the court has the right to ask him. If you ask him again and again about the Khmer Rouge he will just say the same thing. It’s Ok if you come here to ask about his health or how he’s doing—he is fine. Sometimes he gets sick, but he’s Ok. But about the Khmer Rouge? I want to say the following to Phung Ton’s daughter: You have no right to ask about that.”

****

I did not think much about how Sunthary would respond to my failed attempt at an interview with Mam Nai. She would view it, I assumed, as just another in a series of let-downs on a 31-year journey that had yielded very little.

So when I broke the news over lunch, her response surprised me. She said nothing and stared at me for a few minutes, and when I met her gaze I recognised something I hadn’t been expecting: a capacity for genuine disappointment.

Two minutes passed. Then she smiled, sipped her juice and said, “So, he is still afraid to talk. Do you think that maybe after the verdict comes in, and all of the trials are over, and we’re not talking about the tribunal anymore, that Mr Mam Nai might be willing to talk to me about Tuol Sleng?”

I didn’t know what to say, but as I fumbled for an answer I was hit by the paradox of her situation. Here was a woman, after all, for whom the tribunal—touted by the Cambodian government as an opportunity for “those most responsible for serious crimes to be held accountable for their crimes and for the historical record to be set straight”—had become just another barrier to obtaining the information she so clearly needs to move on.

The original version of this article can be found here. Click here for the PDF.

Source URL: http://robbiecoreyboulet.com/2010/06/how-did-phung-ton-die-2/